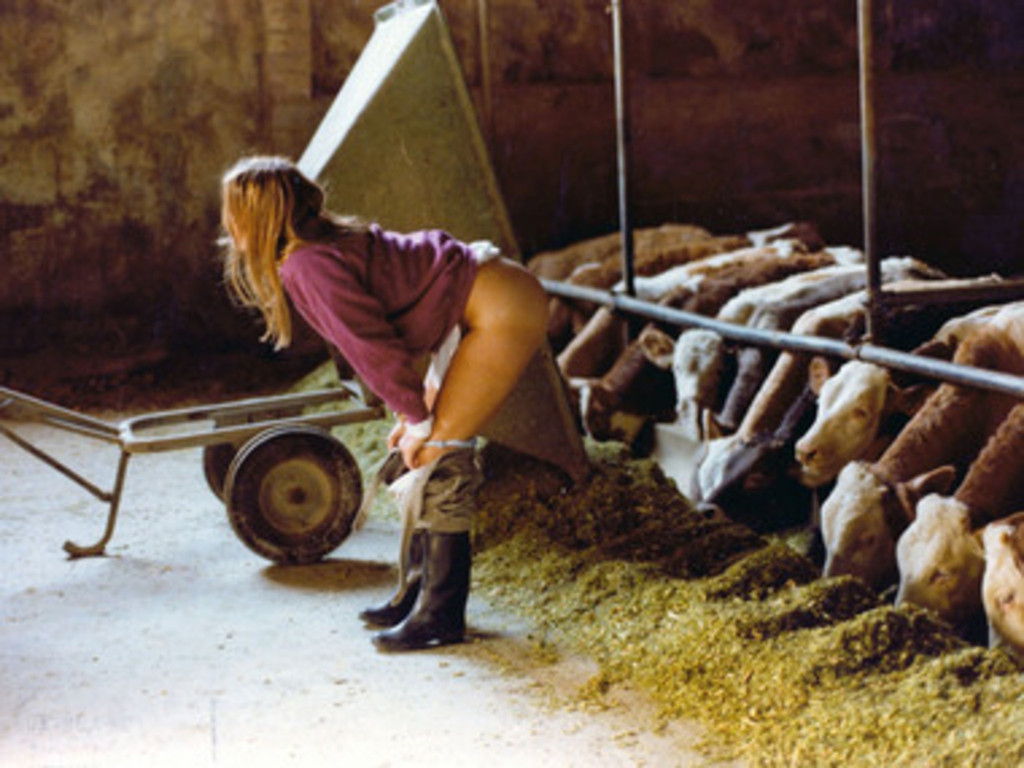

Featured image from Regular Lovers.

I’ve watched more movies than usual the last couple of months, so this film diary installment was feeling pretty unwieldy. I decided to split it into two parts. I am devoting this post to the deep dive I’ve done into May ’68 cinema the last six weeks. In a few days I’ll post again with all the other stuff I’ve watched since early April (spoiler: so much Vincente Minnelli).

The events of May ’68 were momentous for French cinema. In honor of the 50th anniversary, I decided to undertake a survey. Before getting into it, some context:

In 1967, the first workers’ strikes in France since the 30’s took place, and there was a nationwide wave of unionization. At the same time, there was a climactic surge in leftist politics among students. The unions were primarily concerned to increase workers’ wages and quality of life, and they formed an alliance with the PCF (French Communist Party). The student activists included a mix of revolutionary Trotskyists, Maoists, and anarchists who had far more radical goals than the PCF, which favored incremental improvements for workers and an electoral path to power. For a brief moment in May ’68, students and workers staged massive demonstrations together and occupied factories all over France. Violent police responses to initial student demonstrations prompted sympathy from more moderate contingents who then joined into the fray, resulting in a remarkable display of anti-establishment unity. It was enough to shut down the government and national economy and force President de Gaulle to flee Paris. To many, it seemed like the revolution had really come. But it hadn’t. The etiology of the uprising’s collapse is controversial, but the government offered a substantial minimum wage increase and other concessions to unions while threatening military intervention, and the workers gradually gave up the strike and returned to work. The leftist contingents blamed the PCF (who they decried as Stalinists) for caving too readily and fracturing the movement, while the PCF blamed the leftists for unrealistic aims and violent methods that undermined public sympathy. Ultimately, the centrists consolidated power, but many workers did see appreciable improvements in their quality of life. Perhaps most significantly, the cultural and sexual revolutions of the time succeeded in transforming France where the attempted political revolution failed.

On to the movies. I included films that were made in the ’68 milieu by participants in the uprising, films that were made in years following ’68 documenting and critiquing the aftermath, and films that were made many later years looking back on the time period. I think the best films directly about May ’68 and its aftermath are Garrel’s Regular Lovers, Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore, Godard’s Tout va bien, and Rivette’s Out 1 (which I did not rewatch, though I hope to when I get the chance). It’s broader in scope, but Chris Marker’s A Grin Without a Cat is also fantastic and essential. The worst May ’68 film for me is Bertolucci’s The Dreamers. I hate it. I also dislike Assayas’ Something in the Air, and I can’t stand Guy Debord, who made several relevant films and was a leading figure of the Situationist school of thought that was central for the student contingent of the movement.

My favorites are highlighted in bold

Zanzibar Productions

Zanzibar Productions is ground zero for May ’68 cinema. It’s a great story: painter Olivier Mosset spent a year at Warhol’s Factory and came back to France with the idea that artists working in different media should experiment with film. Around that time, Éric Rohmer’s La Collectionneuse brought together poet and critic Alain Jouffroy, sculptor Daniel Pommereulle, and editor Jackie Raynal. Together with Mosset and some other friends from the same underground scene, they started making films. Radicalized heiress Sylvina Boissonnas founded Zanzibar Productions and provided ample funding. Most of the films were made on expensive 35mm film with generous budgets. Pommereulle’s film Vite includes some extravagant shots of the moon filmed through a massive telescope in California (which Marlon Brando introduced him to!). Aside from those already mentioned, the Zanzibar group included Philippe Garrel, Patrick Deval, Étienne O’Leary, Serge Bard, Frédéric Pardo, Pierre Clémenti, Michel Fournier, Michel Auder, Caroline de Bendern, and Zouzou. Because the films didn’t need to make money, and because everyone was preoccupied with taking drugs, making art, and trying to overthrow the old social order, no one tried very hard to promote the films, and they were not screened widely. Many of them sat in a basement until they resurfaced in 2000 and were screened at the Cinémathèque Française. Sally Shafto brought attention to the group with her 2007 book The Zanzibar Films and the Dandies of May 1968, and many of the films are now available on DVD. A few Zanzibar films are still inaccessible; I watched everything I could get my hands on, including later films by members of the group.

Some of these films are not overtly political. They are all rebellious, but in many cases the rebellion is against aesthetic norms. The most overtly political of the bunch is arguably Bard’s Destroy Yourselves. My favorite is probably Deval’s Acéphale. Without further ado, here’s a list of accessible titles with quick comments:

Philippe Garrel

Marie pour mémoire (1967), Le révélateur (1968), The Virgin’s Bed (1969)

Image from Le révélateur

Garrel made four Zanzibar films. La Concentration, with Jean-Pierre Léaud and Zouzou, is nearly impossible to see. He was only 20 years old at the time, and these films manifest his immaturity, but they also highlight how remarkably talented he was from a young age. He went on to have by far the most illustrious career as a filmmaker of any member of the group. These early films attracted critical praise from Jacques Rivette, who aptly described his work as the offspring of Godard and Cocteau. Garrel later cited Rivette himself as a major influence. His other primary influences at this point in his career were Murnau and von Stroheim, and this is especially apparent in Le révélateur, which is probably the best-known Zanzibar film. It’s completely silent, filmed in striking high-contrast black and white, and contains some extraordinary images, but I find it heavy-handed. Marie pour mémoire is his first feature. It stars Zouzou and comprises a series of abstract, interconnected vignettes where young people struggle against various forms of authority. The Virgin’s Bed is my favorite of the three, and is the easiest to access at the moment (last I checked it’s still streaming on Amazon through the MUBI channel). Filmed mostly in Morocco, it features the inimitable Pierre Clémenti as Jesus and Zouzou as Mary Magdalene and reimagines the story of Christ in the late 60’s political milieu (with the counterculture as the saviors of humanity, of course). It has the same issues with immaturity as the other two but it seethes with the energy of the moment.

Jackie Raynal

Deux fois (1968)

Raynal’s film is a bold and fascinating experiment, and one of the most important Zanzibar films. It’s considered a groundbreaking work of feminist cinema. It announces the end of all meaning and then proceeds through a disconnected series of scenes that are repeated two or three times with slight differences. For instance, she repeats a scene three times where she goes into a store to buy a bar of soap. Once she speaks Spanish (the film was made in Barcelona), once she speaks French, and once she speaks a combination of the two.

Patrick Deval

Héraclite l’obscur (1967), Acéphale (1969)

![[CM+Capture+2.jpg]](https://strohltopia.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/209ef-cmcapture2.jpg?w=660)

Image from Acéphale

The former is not an official an official Zanzibar title, but Deval went to Tunisia around the same time to film this poetic short about Heraclitus. It definitely rang my Greek Philosophy nerd bell. The latter, which takes its name from Bataille’s journal, is a surreal work of anarcho-primitivism. I love it.

Serge Bard

Fun and Games for Everyone (1968), Ici et maintenant (1968), Destroy Yourselves (1969–though it was actually the first Zanzibar film produced)

Image from Ici et maintenant

Destroy Yourselves (from the phrase “help us, destroy yourselves,” scrawled on a campus wall) begins by announcing that it was made in April ’68. It’s boiling over with the energy that fueled the May uprising. Alain Jouffroy lecturing to a nearly empty classroom is iconic.

The other two Bard films are even more experimental. I can’t say I recommend Fun and Games for Everyone, which is an ultra-abrasive collage of images and sounds from an Olivier Mosset gallery opening. Ici et maintenant is mostly ravishing black and white seascapes. There’s also some far less interesting material with Caroline de Bendern and Mosset sitting around not doing much.

Pierre Clémenti

La révolution n’est qu’un début. Continuons le combat. (1968)

I love this Clémenti stuff (more below). His one official Zanzibar title is an acid-drenched collage of 16mm footage of the May demonstrations, his friends doing drugs, and lots of other late 60’s imagery. As psychedelic collages go, Clémenti’s are top notch.

Frédéric Pardo

Home Movie: On the Set of Philippe Garrel’s ‘Le lit de la vierge’ (1968)

This is mostly made up of footage Pardo shot while the Zanzibar crew was in Morocco making The Virgin’s Bed. It would appear that he was having a sexual relationship with actress Tina Aumont, as there is a preponderance of intimate footage of her. That stuff is all fantastic, and there are some truly inspired passages, but I felt like the first half of this could have lost some weight.

Olivier Mosset

Un film porno

It’s a 3 minute Warhol-esque snippet with a good punchline.

Étienne O’Leary

Chromo sud (1968)

This is a rather terrifying experimental film with extremely rapid editing, dark imagery, and dissonant ambient music. I don’t think most people would enjoy watching it, but if you’re into this kind of thing….

Daniel Pommereulle

Vite (1969)

This is a beautiful film. It features the above-mentioned shots of the moon through a fancy telescope, and much of the rest of it was shot in North Africa. The director and a young boy spit at the West and make defiant gestures. The exterior of the telescope is compared to a statue of an elephant and there are some shots of mountains, and that’s pretty much it, but it all comes together nicely.

Also:

Zanzibar (Raynal, 2005)

Short documentary catching up with some of the Zanzibar crew many years later. You’ll find it interesting if and only if you are interested in these films. It’s pretty superficial but there are some nice tidbits and it’s cool to see everyone all grown up.

Philippe Garrel continued

Garrel is for me one of the most interesting filmmakers of the last 50 years. I watched through most of his films over the last couple months. The only features I didn’t watch are La Concentration, which is inaccessible, and three of his 70’s experimental films with Nico (Le berceau de cristal, Un ange passe, and Le bleu des origines). I have access to the three 70’s films but in terrible VHS rips and a cell phone video someone shot of a theatrical showing. I can’t bring myself to watch these beautiful films in such terrible quality, but I inspected them and I’m especially eager to see a proper version of Le berceau de cristal. All four of the features I haven’t seen have screened theatrically in NYC over the last couple years, so it’s not hopeless.

Garrel’s career can be roughly divided into three stages. His father, Maurice Garrel, was a successful actor and Philippe started making movies from a young age. First, from the 60’s up till the late 70’s he made non-narrative films that ranged from the political provocation of his Zanzibar work to the pure interiority of Les hautes solitudes. Starting with the 1979 transitional work L’enfant secret, he shifted towards autobiography. His work during from this point on reflects the strong influence of his friend Jean Eustache, particularly his iconic post-’68 film The Mother and the Whore. His autobiographical films are typically fairly abstract and generally have experimental narratives. He often casts his father as his father, his children as his children, and his lovers as his lovers. In one case he plays himself, but usually he casts another actor. His son Louis Garrel developed into an excellent actor, and later in his career Philippe often casts his son as a stand in for himself. For me, Garrel hit his peak in the 90’s, making a series of lyrical, Proustian autobiographical films. In 2005 he made his magnum opus Regular Lovers, which is his most direct later statement on May ’68. His middle period closed with 2009’s Frontier of the Dawn, the last of his many films addressing his relationship with Nico and its aftermath. Since then he’s continued to explore some of the same themes as during his middle period but his narratives have gotten more straightforward. He’s still working, and 2017’s Lover for a Day is great.

Garrel is arguably the filmmaker who has most deeply and extensively explored May ’68. A common theme of his middle-period work is the defining role the event played in the lives of many of its participants. For Garrel, May represents an irretrievable nexus of hope and possibility that cast a lifelong shadow. The worst films about May (I’m looking at you, Bertolucci) look back on the time with shallow nostalgia. For Garrel, May is more like a ghost that haunted the revolutionaries and drove many to kill themselves (either directly or by means of heroin abuse). Eustache’s 1981 suicide looms large, as does Garrel’s own history of heroin abuse (which he and Nico fell into together during their ten year relationship).

Les enfants désaccordés (1964)

Garrel’s first film (he was 16), about young runaways who squat in an abandoned mansion.

Actua 1 (1968)

Short newsreel documenting the May ’68 demonstrations.

Anémone (1968)

The actress who took her name from the film’s title plays a young poet struggling to get out from under her father’s influence. The father is played by Maurice Garrel, who was a hell of a good sport about playing sinister father figures in his son’s films. Not crazy about this one.

The Inner Scar (1972)

There’s a shepherd with a flock, Nico plays a queen on a journey, and a naked Pierre Clémenti rides around on a horse wielding a bow and arrow. It’s a little like Jodorowsky, but much more lyrical and I like it a lot more.

Les hautes solitudes (1974)

I consider this a masterpiece. Most online summaries make the bizarre mistake of describing it as a documentary about Jean Seberg. That’s just false. The concept here is to compile a series of outtakes from a film that doesn’t exist. Four performers appear in the film at least briefly (including Nico), but it consists almost entirely of shots of Seberg feeling emotions. It couldn’t have worked as well with anyone but her. It’s utterly mesmerizing.

L’enfant secret (1979)

Garrel’s transition to narrative cinema. Before her relationship with Garrel, Nico had a child with Alain Delon, who refused to acknowledge paternity. The child grew up with Delon’s parents. This film is about the effect this separation from her child had on Nico, and the resultant effect on her relationship with Garrel. The narrative is elliptical, and the child just shows up every now and then without explanation. It’s a remarkable film, and absolutely essential for anyone exploring Garrel’s filmography.

Liberté, la nuit (1984)

Garrel’s tribute to his politically radical parents and his one film directly about the Algerian war. It’s quite abstract, and Maurice Garrel’s performance is astonishing. Emmanuelle Riva (as the mother character) is not in the movie as much but she has some incredible scenes.

Rue Fontaine (1984)

A devastating short (part of the omnibus film Paris vu par… 20 ans après), starring Jean-Pierre Léaud and Christine Boisson.

She Spent So Many Hours Under the Sun Lamps (1985)

Garrel’s dreamy reckoning with Nico’s death, and the first of several films evoking Proust’s The Fugitive in their portrayal of his inability cope with her loss (even though they had parted ways years earlier and he had since married Brigitte Sy and had a child with her). Godard’s ex-wife Anne Wiazemsky plays the Nico stand in, and directors Jacques Doillon and Chantal Akerman appear in small roles.

Emergency Kisses (1989)

This is autobiography-core. It reflects the influence of Rivette’s L’amour fou. Garrel himself plays the film director, his wife plays his wife, his father plays his father, and his son plays his son. It doesn’t get much more meta: the director is making an autobiographical film, and casts an actress other than his wife (namely, Anémone) as his wife, which strains his marriage. Like in many of his films from this period, Garrel portrays himself as kind of a piece of shit. It’s bold and unsettling.

I Can No Longer Hear the Guitar (1991)

This is just perfection. May ’68 is always under the surface in Garrel’s autobiographical films, but here it is made explicit. He works in color for a change, with stunning cinematography by Caroline Champetier. The narrative is very elliptical in a similar manner as we often find in Claire Denis. The film shows us glimpses of a man’s life over the course of many years, including episodes resembling Garrel’s relationship with Nico, his heroin addiction, his marital infidelities, and his lifelong post-’68 hangover.

The Birth of Love (1993)

Lou Castel and Jean-Pierre Léaud play two middle aged friends from the ’68 generation living in Paris. The former is haunted by his one true love while the latter is discontent with his relationship and perpetually unfaithful. It seems to be an attempt by Garrel to negotiate the conflict between his own romanticism and perpetual discontent.

Le coeur fantôme (1996)

I get the sense that this one is pretty neglected. I really don’t see why: for me this is one of Garrel’s best. This is the point where the depth of his Proustian sensibility became apparent to me. It’s about a painter who takes up with an unstable younger woman, and delves deeply into the role of jealousy in grounding attachment, the way that our sense of self can be bound up with connections to others, and the way that the loss of a relationship can be a sort of death.

Le vent de la nuit (1999)

The most potent of Garrel’s many films about suicide and a masterpiece of post-’68 cinema. Daniel Duval plays a suicidal sculptor who has post-traumatic stress due to enduring electro-shock therapy as a consequence of his May ’68 activities. Duval’s character meets a young sculptor who uses recreational drugs and lives for the moment and brings him along on a couple long drives. The young sculptor is the lover of an older woman played by Catherine Deneuve—another suicidal member of the ’68 generation—and eventually he introduces Duval’s character to her and they share a brief but extraordinary connection. This totally wrecked me.

Wild Innocence (2001)

A bizarre foray into high concept filmmaking, I consider this to be one of Garrel’s weakest films. A filmmaker who has lost a lover (another Nico stand in) to heroin abuse seeks to make an anti-heroin film. To fund the film, he ends up getting roped into smuggling heroin, and the innocent, inexperienced actress he casts as the Nico character ends up becoming a heroin addict in the course of making the film. This is the first film where Garrel’s daughter Esther appears (she’s still a child at this point). Like his son Louis, she’s become a successful actress.

Regular Lovers (2005)

For me, the single most poignant moment in all of May ’68 cinema is the scene in Regular Lovers when the police show up to discuss some trivial matter and the protagonist’s terror at encountering law enforcement fades into the crestfallen realization that he’s no longer an outlaw. Filmed in rapturous black and white by the great William Lubtchansky, this three hour epic feels like a summation of Garrel’s entire career up till this point. The abstract early scenes portraying the May unrest highlight what a disgrace the ending of The Dreamers is. This is how you do it, Bertolucci. The structure of the film is relatively straightforward: we start with May, and then we follow the protagonist (Louis Garrel standing in for his father) as he tries to sustain the freeness of the revolt while he goes on with life, but loses himself as he becomes consumed by a romantic relationship and by opium addiction. Godard recently said at Cannes that this is the greatest ’68 film, and he would know. It’s a tremendous shame that The Dreamers is the film through which most Americans of my generation are acquainted with May ’68. It should be this.

Frontier of the Dawn (2008)

Again featuring cinematography from Lubtchansky, this is yet another evocation of The Fugitive, but more abstract and less directly autobiographical. Last I checked, this is on Hulu. It’s an excellent film.

A Burning Hot Summer (2011)

This title seems to be less critically successful than most of Garrel’s other work, but from what I’ve read the complaints seem pretty off base. I really like Neil Bahadur’s take on this one. As he aptly points out, the key points of reference here are Godard’s Contempt, Rosselini’s Voyage in Italy and Rivette’s Don’t Touch the Axe (aka The Duchess of Langeais). I also noticed several Mulholland Drive references. The dancing scene is one of the greatest things Garrel ever filmed. Monica Bellucci is excellent.

Jealousy (2013)

The first in Garrel’s recent trilogy of ~70 min films about relationships. Blake Williams points out that this seems to be about Garrel’s father’s infidelity decades earlier. This is good, but minor.

In the Shadow of Women (2015)

Better than Jealousy but not as good as Lover for a Day. Like A Burning Hot Summer, it examines a selfish man (surprise, a filmmaker) who refuses to be faithful but who is extremely jealous of his partner.

Lover for a Day (2017)

An older philosophy professor has a relationship with a student his daughter’s age. The daughter is played by Garrel’s actual daughter Esther. One of the most beautiful films in recent memory.

Pierre Clémenti continued

Visa de censure n° X (1967), New old (1979), In the Shadow of the Blue Rascal (1986), Soleil (1988)

Image from In the Shadow of the Blue Rascal

Pierre Clémenti is best known for his acting work (you might remember him from Bunuel’s Belle de Jour), but he was also a hell of a filmmaker. Like his Zanzibar film mentioned above, Visa de censure n° X is a psychedelic collage with an acid rock soundtrack. This is not the kind of thing I’m generally into, but Clémenti hits it out of the park. Lots of shots of his friends enacting pagan rituals. In the Shadow of the Blue Rascal is his only feature length film, and it’s a sort of surrealist, dystopian sci-fi low budget masterpiece. It’s set in a place called Necrocity and Jean-Pierre Kalfon plays a Mabuse figure named Captain Speed. The music is amazing. The ’68 connection with the later stuff is more tenuous but it’s there—in the portrayal of sinister, omnipresent, oppressive authority.

Godard

I’ve been chipping away at my many Godard blind spots pretty steadily over the last six months or so, and my stamina for his more challenging work is improving. I finally got through A Film Like Any Other after trying and failing a few months ago. He made a lot of films that are relevant to May ’68. Some of them were covered in previous film diaries, and there are a few I haven’t watched yet, but I’ve seen all the most directly relevant stuff. He collaborated with Jean-Pierre Gorin (a student of Foucault, Althusser, and Lacan) on a lot of these titles. I won’t bother to note exactly where, since Gorin isn’t always credited and it’s confusing.

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967), La Chinoise (1967)

Godard made three films in 1967 that anticipate May ’68. The third is Weekend, which I didn’t revisit for this piece. I’d highly recommend it as an initiation to his radical period (it’s far more accessible than what came after it). These two are both essential. 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her is a broad indictment of the sorts of problems with modern life that animated the May revolt. Like several of Godard’s other films, its presents prostitution as a metonymy of consumer culture. La Chinoise depicts Maoist students incompetently attempting to be terrorists. Godard was generally quite critical of the student movement for its frivolity and faux seriousness, but here he acknowledges that the students are at least on the right track, and encourages them to keep trying.

A Film Like Any Other (1968)

This is rough to get through. It’s mostly the backs of peoples’ heads for two hours as they sit in a field and discuss the divergent goals of the workers and students involved in May ’68. At least—unlike Debord (see below)—Godard takes the workers seriously and grasps that a proletarian revolution can’t be achieved by ideologue students seizing the role of paternalistic puppeteers to a childish working class who don’t understand what’s in their own best interests.

Le gai savoir (1969)

Godard called this his last bourgeois film, presumably because it’s got reasonably high production value and stars well-known actors (Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliette Berto). It’s a transitional work, where he tries to destroy his old ideas to make way for new ones. A common theme between this and the Dziga Vertov group films (esp. Struggle in Italy and Wind From the East) is that Godard doesn’t know how to make anything but bourgeois cinema and is trying to free himself from the snare of his cinephilia. There’s an underacknowledged humility in this approach: his films from this period all announce themselves as failures. He can’t stop making films, that’s the only thing he knows how to do, but he can’t make films that succeed at what he’s trying to accomplish, which is to create a revolutionary cinema. Again, I would highlight the contrast with Debord, who thinks he already has all the answers.

Struggle in Italy (1971), Vladimir and Rosa (1971)

Dziga Vertov Group films, probably not appealing to most people. They are not supposed to be enjoyable. The former is a critique of an Italian student (standing in for students in general) trying to make the class struggle a part of her daily life but ultimately collapsing back into bourgeois ideology. Godard is often accused of misogyny, and this is a good bit of evidence for the charge, as he seems to be especially contemptuous of the character in virtue of her gender. Vladimir and Rosa is a gonzo reenactment of the Chicago 8 trial, with Godard as Lenin and Gorin as Rosa Luxemburg.

Tout va bien (1972)

Godard and Gorin with a real budget (which they explain at the beginning they got by selling out and casting Jane Fonda). I’m not hardcore enough to prefer the other DVG films over this. I’m happy to see Godard let himself be cinematic again, particularly in his Tati-esque imagining of a revolt breaking out in a grocery store. This film is concerned in general with the way that the ’68 movement was reassimilated into bourgeois ideology. It’s also an exhortation not to give up.

Every Man for Himself (1980)

Not really a May ’68 film but I’m including it with the rest of the Godard I watched recently. This is the first movie Godard shot on film after a long stretch of low-budget video experiments. He called it his “second first film.” It’s extremely good and rather crass. It returns to Godard’s frequent theme of prostitution, and draws some brash connections between film and television direction and sexual exploitation. Awesome performance from Isabelle Huppert.

Guy Debord

Fuck Guy Debord. I hate this guy. Just read this shit: http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/debord.films/refutation.htm

Debord was a leading figure in the Situationist movement, which was immensely influential for the student contingent of May ’68. Very roughly, the Situationists were concerned to critique the omnipresence of consumer capitalism in everyday life (particularly the way that representation replaces direct experience—The Spectacle) and seeks the creation of Situations (I know, very helpful term) that somehow break through The Spectacle and achieve (poorly defined) authenticity. One of the key ways of accomplishing this is detournement, where The Spectacle is turned against itself and used to reveal its own nefariousness. Basically: Debord hates movies, and he makes movies that reuse bits of other movies to show how all movies not by him are part of this oppressive consumerist Spectacle.

I was particularly irked by the Situationist screed against Godard: http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/10.godard.htm

Debord adopts an utterly condescending tone regarding workers. He wants a proletarian revolution where the proletariat stays out of it and narcissistic intellectuals call all the shots. It’s hard to find a more dogmatic philosopher with fewer arguments than Debord. There are some interesting observations here and there (particularly the stuff about Stalinism and bureaucracy), but mostly it’s profound-sounding obscurity that fails to address even the most obvious and basic objections. By contrast, Godard’s radical period is the opposite of dogmatic. It’s exploratory and characterized by humility and self-reflection. He can come across as ultra-didactic, but he’s always undermining and rejecting his own didacticism. Debord is very sure about already having everything figured out.

Hurlements en faveur de Sade (1952)

This is a prank film. It’s mostly just a black screen, and then there are bits of white screen with some narration about love in the time of revolution or “hurray de Sade!” and then it’s cut off and there’s more black. It ends with like 20 minutes of black screen and silence. The point is supposed to be that cinema is dead, meaningless, blah blah blah. I think it sucks.

On the Passage of a Few People through a Relatively Short Period of Time (1959), Critique of Separation (1961)

Blah blah blah there’s no authentic connection between people under capitalism, movies are bad.

The Society of the Spectacle (1973)

Here he reads from his influential book by the same title over a montage of images from other films. In his response to all judgments of this film (linked above) he basically says that you’re only capable of liking it if it’s the only film you like. That should tell you everything you need to know.

Jean Eustache

The Mother and the Whore (1973), Mes petites amoureuses (1974)

Image from The Mother and the Whore

These are the only two narrative features Eustache made, and they’re both masterpieces. The Mother and the Whore is a 3.5 hour autobiographical post-May ’68 epic. Cahiers du Cinéma named it the best film of the 70’s. Jean-Pierre Léaud plays a revolutionary turned man of leisure who lives off of his girlfriend (Bernadette Lafont) while bumming around cafes. He begins an affair with sexually liberated nurse Veronika. I won’t give the rest away but the film is concerned with the downsides of the sexual revolution, which is not to say that it regrets the sexual revolution. It’s sometimes read as a very conservative film, but I don’t think this is right. It’s much more ambivalent than that. Anyways, it’s a very hard movie to blurb and you should just see it. Due to issues with Eustache’s estate it’s not easy to access, but it’s a mainstay in repertory theaters and there’s a perfectly acceptable rip circulating online (beware: some versions are cropped, but there are good ones out there. They all share a source with a single isolated glitch, which is annoying but shouldn’t be a deal-breaker).

Mes petites amoureuses isn’t really a May ’68 film, but it’s not unrelated, since it deals with the plight of the working class. It’s also autobiographical, and relates the story of a young boy who is raised by his grandparents but then has to move to the city with his deadbeat mom and work for no pay at a repair shop owned by her boyfriend’s brother. He becomes more interested in girls and has his first few clumsy sexual encounters, marked by increasing boldness on his part. This film could be seen as the third part of a sequence that began with Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and continued with Pialat’s L’enfance nue (note that Pialat appears here in a small role). It is separated from the other two by its austere Bressonian style (in its acting, blocking, and framing especially). It’s extremely different from The Mother and the Whore, but they are both truly great films.

Chris Marker

A Grin Without a Cat [Le fond de l’air est rouge] (1977)

Marker’s three hour documentary is an exceptional compendium of global political turmoil from the late 60’s through the mid 70’s. It covers a lot of ground, including the Vietnam war, the Cuban revolution, Che’s death in Bolivia, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, May ’68, the Prague Spring and subsequent Soviet invasion, violent suppression of pre-Olympic protests in Mexico city, and the 1973 Chilean coup.

Marker is concerned with three struggles that characterized the time: reactionaries vs. revolutionaries, guerrillas vs. incrementalists, Stalinists vs. reformists. Perhaps the highlight of the film is a remarkable interview with Castro, who sides with the Stalinists but appears conflicted.

Note that there are three versions of this. The original version is four hours long. Marker later edited it down to three hours, and then this three hour version was dubbed into English. Avoid the dubbed version! The narration is terrible compared to the original three hour cut. I’m curious to see the four hour version.

À bientôt, j’espère (1968, with Marret), Class of Struggle (Medvedkine Group, 1969)

The first of these documents a strike at a textile factory in Besançon in March 1967. It was the first workers’ strike in France since the 30’s. One gets a clear idea of what the workers’ concerns were. It’s not primarily about money, though money is part of it. It’s more about making work compatible with a full and balanced life. To return to my tirade against Debord: his denunciation of unions, which he saw as a way for workers to pursue contemptible bourgeois goals, feels especially nauseating when one relates it to this film. He’s purportedly interested in restoring authentic experience but passes judgment on workers for wanting to be able to spend time with their families? The second film revisits the same factory after the events of ’68. A mild-mannered woman we met in the first film has become a leading labor organizer and now has a poster of Castro on her wall at home. We learn about her efforts and how the factory has punished her for them.

Miscellaneous

1968 (Rocha and Beato, 1968)

Unfinished newsreel footage of protests in Brazil.

Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (Tanner, 1976)

Swiss ensemble film about people who were involved in May ’68 and have since settled into disappointing lives where they try to keep the revolution alive in small ways (even just in daydreams). This was a little tepid for me.

Grands soirs & petits matins (Klein, 1978)

Remarkable fly-on-the-wall footage of the uprising, including meetings, protests, debates, etc. This was screened in a few theaters for the first time with English subtitles earlier this year but it’s still not possible to see it with subtitles at home. I watched some of it, but my French isn’t good enough to understand people shouting over each other and talking really fast in angry tones about the bourgeoisie. Some familiar faces show up, including Resnais and Rivette. Perhaps the most telling moment in what I saw shows a female student being shut down by the endlessly ranting male rhetoricians when she tries to speak up.

Half a Life (Goupil, 1982)

This also includes footage from the uprising. It’s framed as a portrait of the filmmaker’s friend Michel Recanati, a militant student leader during May ’68 who later committed suicide. This true story lends vividness to the sort of arc that we often see portrayed in Garrel. What I found most interesting about this movie was how forthcoming it is about the lack of intellectual rigor of the movement. Think Bernie bros. Student militants were happy to just make things up or distort history. The point was to be loud and persuasive and stir up revolt, not to think things through carefully.

May Fools (Malle, 1990)

Delightful comedy from Louis Malle, starring Michel Piccoli and Miou-Miou. The elderly owner of a dilapidated estate dies just before the events of May ’68 and the whole family gathers to bury her and execute her will while protests flare up in all over France and close in around them. One of the sons shows up fresh from the Paris barricades with tales to tell and everyone starts flirting with each others’ significant others. It becomes a Smiles of a Summer Night-style sex comedy and the family becomes convinced that the revolution is about to show up on their doorstep, with hilarious results. Of the more frivolous ’68 movies, this is my favorite.

The Dreamers (Bertolucci, 2003)

I saw The Dreamers in the theater when it came out, but hadn’t seen it again until recently. I’ll give it one thing: Louis Garrel is pretty good. The other two leads (Eva Green and Michael Pitt) are remarkably bad. The cinematography is like a shitty William Lubtchansky imitation with none of the grace. The writing is in the running for worst of all time.

“I was one of the insatiables. The ones you’d always find sitting closest to the screen. Why do we sit so close? Maybe it was because we wanted to receive the images first. When they were still new, still fresh. Before they cleared the hurdles of the rows behind us. Before they’d been relayed back from row to row, spectator to spectator; until worn out, secondhand, the size of a postage stamp, it returned to the projectionist’s cabin. Maybe, too, the screen was really a screen. It screened us… from the world.”

I can’t believe someone sat down and wrote that and then thought, “yeah, that’s good, I’m going to go with that.”

“I’ve always wanted to make love to the Venus de Milo.”

I can’t even. The situation is just so false in every way. This brother and sister who live in a two-person intimacy cave meet a random American and immediately invite him and only him to join in? Because he’s a cinephile? There are no other cinephiles around? It felt like grotesque fantasy pandering: just show up at the cinema in Paris and a busty, hypersexual virgin will recite Garbo dialogue and invite you to unceremoniously deflower her on the kitchen floor.

The May ’68 backdrop highlights how vapid the whole thing is. This movie does exactly jack shit to illuminate the historical moment.

Something in the Air (Assayas, 2012)

Also vapid, but much better than The Dreamers. I was very disappointed by this. There are a few Molotov cocktails but mostly it’s Assayas reminiscing about girls he slept with. It opts for shallow romanticism and nostalgia where Garrel finds an existential abyss.

In the Intense Now (Salles, 2017)

Sort of like a shorter, more personal and less accomplished Grin Without a Cat from a Brazilian perspective. It features footage of the Cultural Revolution from the filmmaker’s mother. The most interesting thing here for me is the footage of the counter-protests held by members of the bourgeoisie during May ’68 after a speech from De Gaulle. They actually turned out in larger numbers than any other single demonstration during May.

Cheers for the marvelous publishing! I must say i liked looking at it, you happen to be an excellent author.

LikeLiked by 1 person