This is the initial draft of my contribution to the upcoming volume Life Above the Clouds: Philosophy in the Films of Terrence Malick (ed. Steven Delay, SUNY Press). The hardback is coming out early in 2023, with a paperback and ebook to follow early in the summer.

***

Malick’s run of films from 2011 through 2017 (Tree of Life, To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, Voyage of Time, and Song to Song) are among the most polarizing works in contemporary cinema. This is no surprise to me, because they are at once formally challenging and blissfully unfashionable in their lofty spiritual orientation. These films are characterized by notable stylistic continuity, particularly To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song, which were all filmed without a script and edited in a similar style. Tree of Life and Voyage of Time also bear certain strong affinities, both to each other and to the other three, but are distinct in that Tree of Life was filmed with a script and has a more cohesive and legible narrative, while Voyage of Time is an experimental documentary with no traditional narrative at all.

Commentators have identified two possible trilogies among these films. Tree of Life, To the Wonder, and Knight of Cups have been seen as an autobiographical trilogy, paring episodes from Malick’s life with spiritual themes.[1] Roughly, Tree of Life pairs his brother’s untimely death with themes including grace and the problem of evil, To the Wonder pairs his first marriage and his reunion with an earlier love with themes including God’s silence and the way that suffering can enable spiritual progress, and Knight of Cups pairs his early years as a Hollywood screenwriter with themes including worldly temptation and spiritual awakening. Others have suggested that To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song constitute a trilogy. Commentators including Michael Joshua Rowin and Robert Sinnerbrink refer to these three films as the “Weightless Trilogy,” after the original title of Song to Song.[2] These films are connected by their unscripted, improvisational style, contemporary setting, thematic purview, and experimental editing.

Our only clue from Malick himself is that he has explicitly denied that he thinks of the first three films as an autobiographical trilogy. His longtime friend Jim Lynch asked him directly. According to Lynch, “He didn’t like me labeling them that way. He didn’t want people thinking that he was just making movies about himself. He was making movies about broader issues.”[3] Notably, he did not correct Lynch by telling him that the latter two films in fact belong to an unfinished trilogy. My own take is that there is some sense in which all of these films should be grouped together. Tree of Life is in part about spiritual crisis. It poses the problem of evil in reference to a staggering personal loss. The film resolves with a sense of hope, and the so-called “Weightless Trilogy” seizes upon this hope and examines various stages of the process of spiritual (re)awakening, while Voyage of Time follows a different strand from Tree of Life, concerning nature and its relationship with divinity.

As this volume illustrates, there are many fruitful ways of approaching Malick. It takes the effort and expertise of more than one person to work through these films. In this chapter, my aim is modest. I want to consider at length the relevance of Plato’s myths of Eros to Knight of Cups and Song to Song. I do not aim to give totalizing interpretations of these films (each of which could support a book-length treatment), but only to shed light on this connection and its broader significance. The importance of the passage from the Phaedrus that is included in Knight of Cups (read aloud by Charles Laughton) has been remarked on by many commentators, including Robert Sinnerbrink, who argues that the Plato’s myth of Eros from the Symposium and Phaedrus “provides an orienting allegorical frame” for To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song.[4] He cites Paul Comacho’s observation that the lovers’ ascent of the steps of Mont Saint-Michel evokes the ascent passage from the Symposium at 210a-212c, and discusses the relevance of the Phaedrus and of Kierkegaard’s version of a Platonic theory of love.[5] Sinnerbrink’s work is illuminating, and I do not here mean to contest it, but only to supplement it with more detailed consideration of the Phaedrus and Symposium and their relevance to Knight of Cups and Song to Song, which were filmed back-to-back and which I take to be especially closely connected.[6] In particular, further exploring the significance of the Platonic theory of love in these films will shed light on the relationship between erotic love and spiritual (re)awakening. Also, while the connection between Knight of Cups and the Phaedrus is explicit, the relevance of Plato to Song to Song is more obscure. Careful attention to the way Platonic motifs from Knight of Cups are carried through in the subsequent film helps to make sense of a number of details that I take to be crucially important.

***

Knight of Cups depicts the Hollywood initiation of Rick, an up and coming screenwriter played by Christian Bale. Its narrative is divided into eight episodes, each of which (save the last) is titled after a tarot card and features a significant person from Rick’s past or who he meets along the way. Two texts function as structuring touchstones: the Gnostic Hymn of the Pearl and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. Both of these connections are discussed at length in Lee Braver’s essay “Transcendence,” also found in this volume.

Nearly all commentators and critics emphasize negative aspects of Malick’s portrayal of this Hollywood lifestyle. David Sims, writing for The Atlantic offers a typically simplistic interpretation of the film’s thematic concerns:

“The point here is that Hollywood is a draining, disorienting, empty place, where even the freest creative spirits can get lost. That doesn’t feel quite as profound or revelatory as some of the insights into the human condition Malick has made in the past, but it’s a message fully received as viewers bounce from party to photo shoot to bedroom escapade.”[7]

Indeed, portrayals of the soul-sucking emptiness of Hollywood are a dime a dozen. Malick’s film would not be very interesting if that’s all it were about. But what Sims and other commentators misunderstand—and what a closer look at the Platonic context can help to illuminate—is that the film portrays most of Rick’s Hollywood escapades as positive steps in a process of spiritual awakening. In many of Plato’s dialogues, including notably the Phaedo, he is pessimistic about the prospects for attaining divine knowledge during a mortal life. In the Symposium and Phaedrus, however, not only do we find a more optimistic perspective, but we find the idea that erotic attraction is a crucial step in the process of attaining such knowledge. Before discussing this aspect of the film, however, it will be helpful to consider in detail the Phaedrus passage that is directly quoted in the film, along with relevant passages that provide important context.

Early in Knight of Cups, during the segment labeled “The Moon,” we see Rick driving a convertible while a woman, Della, spreads her arms and mimics flight. They visit an aquarium where we see rays spread their wings and “fly” towards the light, and we hear Charles Laughton reading an elided passage from the Phaedrus:

“Once the soul was perfect and had wings and could soar into heaven where only creatures with wings can be. But the soul lost its wings and fell to earth, ere it took on an earthly body. (. . . ) [W]hen we see a beautiful woman, or a man, the soul remembers the beauty it used to know in heaven and (. . . ) the wings begin to sprout and that makes the soul want to fly but it cannot yet, it is still too weak, so the man keeps starting up at the sky like a young bird that has lost all interest in the world.”[8]

If another filmmaker included this passage in their film, we might assume that they simply took a few lines that they liked out of context and did not read the rest of Plato’s dialogue or think about the broader implications of the passage. But this is surely not an assumption that we should make for Malick. Indeed, we can safely assume that he closely studied the Phaedrus and thought carefully about the context in which this passage is imbedded.

This passage clearly signals that we should take some or all of Rick’s amorous encounters in the film as reminders of the beauty that his soul “used to know in heaven,” and as catalysts for his spiritual (re)awakening. As Naomi Fisher discusses in her chapter in this book “Tending God’s Garden: Philosophical Theme’s in Malick’s Tree of Life,” this passage references Plato’s ideas about the immortality of the soul and what’s known as the “theory of recollection.” This theory, developed in the Meno and Phaedo, holds that the soul possessed knowledge of the true nature of reality before it was incarnated in a human body. In the Phaedo, Socrates characterizes this knowledge as knowledge of the Forms. The Forms are eternal, immaterial, immutable beings that are perfect and unmixed. The Form of the Beautiful is not one beautiful thing among many. The Form is, as it were, the true essence of beauty; other things are beautiful only to the extent that they resemble it or share in some way in its nature. The Forms are what ultimately ground the world of experience that we access with our senses. Things in the world appear big or small according to the extent to which they share in the Form of the Big and the Form of the Small. The world of Forms is the true reality; the world of experience is its illusory refraction.

In the Phaedo, Plato is pessimistic about the possibility of gaining any true knowledge of the Forms during a mortal life. The needs of the body distract us while our senses mislead us. We are prone to confuse appearance for reality and deny the existence of anything beyond the reach of our senses. At Theaetetus 155e, Socrates describes a class of people he calls “the uninitiated” as those who “believe that nothing exists but what they can grab with both hands.”[9] In the Phaedo, Socrates argues that our senses cannot lead us to knowledge of the Forms and that the path of the philosopher is to try as far as possible to separate the soul from the body by shirking the temptations of worldly pleasures in favor of activities of the soul that are necessarily imperfect, but that at least are a way of striving toward the realities that the soul knew before it was embodied.

In the Symposium, we find a stunning reversal. In Diotima’s speech—which is conveyed by Socrates and which is standardly taken to express Plato’s own views about love (eros)—not just sensory experience, but erotic attraction is presented as a legitimate path towards knowledge of the Forms. At 210a, Plato writes, “A lover who goes about this matter correctly must begin in his youth to love beautiful bodies.” Diotima goes on to describe the lover’s ascent from love of one beautiful body, to love of all beautiful bodies, to an appreciation that the beauty of souls is superior to that of bodies and thus to love of the laws and institutions that make the soul beautiful, to love of abstract theoretical knowledge, and finally to love of the Form of the Beautiful itself. Ascent imagery (e.g., walking up a hill or set of stairs towards the light) is everywhere in late Malick, but it cannot be understood in purely Platonic terms. The higher reality that Malick’s spiritual seekers strive for must also be understood in reference to Judeo-Christian scripture and a range of other references and mythologies.

Near the beginning of Knight of Cups, before the Phaedrus passage is read aloud, we see a black-and-white stop motion video being played in the background at a Hollywood party. We cut to this video and see a woman with two X’s on her back, suggesting the spots where the soul’s wings have been cut off (as described in the Phaedrus). We also see this woman wearing a mask of her own face on the back of her head. This also seems to be a Platonic reference. In Aristophanes’ speech in the Symposium, he describes an earlier time when human beings had two faces, four arms, and four legs. This earlier form of human was powerful, and their power made them arrogant enough to challenge the gods. As punishment, Zeus cut them in half and turned their heads around so that they faced forward. Eros, according to this myth, is a desire to be returned to be reunited with our other half—to be whole again. The image in Knight of Cups of a woman with a mask of her face on the back of her head suggests this desire to return to our original nature.

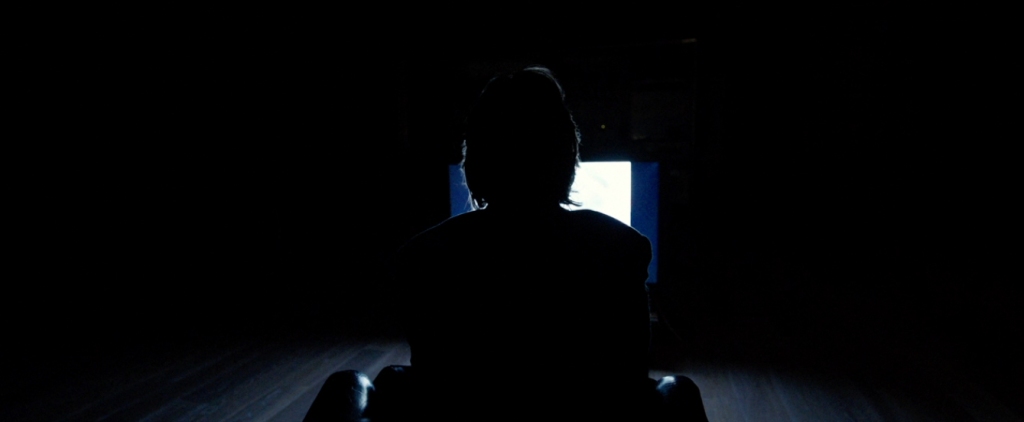

After the stop motion segment, we see a mountain crowned with light, and then we cut to Rick in the midst of a literal earthquake, suggesting a jarring awakening from spiritual slumber. He walks through empty studio lots—a pilgrim in the land of illusion—and then we see him from behind, sitting and watching images of the sky on a television set. This is another Platonic allusion, suggesting the famous cave allegory from Republic VII. The denizens of the cave are stuck watching shadows of puppets, which are themselves imitations of a higher reality. This allegorizes the epistemic condition that human beings are in by default—we confuse our sensory experiences for true reality, when in fact they are a reflection of an imitation of the Forms themselves. Rick is drawn towards the light—but at this stage of his development it is merely an image of the sky, which is itself merely an image of the divine light.

With this context in mind, it is easier to see that Rick’s series of romantic and sexual entanglements in Knight of Cups should not be understood simply as a critique of the shallowness of the Hollywood lifestyle. It’s just the opposite; at least some of the beautiful people who Rick is drawn to should be understood as leading him towards a higher way of being.

This interpretation needs to reconciled with the prominence in the film of the Hymn of the Pearl, which suggests that the people Rick meets in LA fill his glass with intoxicating drink, so that he is lulled into a waking sleep where he has forgotten the path of the spirit. I certainly do not mean to suggest that everyone Rick meets helps him further along the path of his ascent. There are a number of clearly negative figures in the film, including the producer Herb (anticipating Cook in Song to Song) who offers him a Faustian bargain: if he writes whatever junk they ask him to, he can have it all. Malick emphasizes throughout the film that Hollywood is a land of illusion where it is easy for the pilgrim to be led astray. The point, I take it, is that amidst this setting, some of the people who he meets lift his spirit rather than bogging it down. One of the recurring motifs in the movie is that we see the women who Rick is involved with walking away from him and looking back towards him. These shots suggest that they are leading him along his path.

Antonio Banderas, who is featured (as “Tonio”) in the segment titled “The Hermit,” is usually taken to be a negative figure in the film. He is the wealthy host of a debauched party that is staged in the style of Fellini. He tells Rick, “Myself, I didn’t want to get a divorce. I never stopped loving them, but the way I loved them changed. They are like flavors. Sometimes you want raspberry, then after you get tired of it, you want some strawberry.” Of course, it’s natural that Tonio’s horrifying comparison between women and fruit flavors would be taken negatively, but having the Symposium in the background changes the inflection of this line. The first stage of the lover’s ascent is love of one beautiful body, but then in the next stage, “…he should realize that the beauty of one body is brother to the beauty of any other and if he is to pursue beauty of form he’d be very foolish not to think of the beauty of all bodies is one and the same. When he grasps this, he must become a lover of all beautiful bodies, and he must think that this wild gaping after one body is a small thing and come to despise it” (Symposium 210a-b). Tonio’s other most significant line is, “The world is a swamp; you have to fly over it.” This is a clear reference to the swamp of Pilgrim’s Progress, a negative location where the pilgrim gets mired in worldly muck. This line points strongly to the thought that Tonio is in fact an ambivalent figure. Love of all beautiful bodies is not the final stage of the ascent, but Plato does understand it to be a progression from the love of one beautiful body. In the highest stage of the ascent, the lover’s object becomes the Form of the Beautiful itself. The earlier stages are progressions away from the attachment to particular terrestrial manifestations of beauty and towards its divine essence. Fixation on one beautiful body conflates an instance of beauty with the thing itself, and shifting from “wild gaping” after one object of love to the realization that all beautiful bodies are equally worth of love is a progression towards love of the Form of the Beautiful. Tonio emphasizes that he didn’t stop loving the women he divorced; he rather expanded his love to something more general. While Plato’s ideas about love may be jarring in a culture that emphasizes monogamy (this is, after all, the same thinker who argues in the Republic that reproduction among the rulers and soldiers of the ideal city should be done by lottery, with children being raised in common), the most likely interpretation of Tonio’s significance in the film is that he is a lover of beauty who has only progressed to the second stage of the ascent. This is not very far, but it’s farther than most people. He is a shallow man in the grand scheme of things, but he is still higher up than almost everyone around him, and so he can “fly over” the swamp that they are stuck in.[10]

Returning to the Phaedrus, it’s worth taking a moment to unpack the context in which the passage referenced in Knight of Cups is found. It is part of the second speech that Socrates gives about love in the dialogue, standardly referred to as the palinode. A palinode is an ode that doubles as a retraction. In this case, Socrates is retracting his initial speech where he argued that is better to spend one’s time with a lover than a non-lover, because a lover wishes for their beloved to be hindered in various ways in order to increase their dependence on them. At 242d-243a, however, Socrates corrects himself and argues that because Love (Eros) is a god and nothing divine can be bad in any way, his earlier speech must have been mistaken. He presents the palinode as a rite of purification that he must conduct in order to cleanse his earlier offense.

Socrates begins the palinode by diagnosing what led him to his earlier mistakes about the nature of Love. He had thought that because the non-lover is sane and the lover is mad, one should prefer the company of the non-lover (244a). But he now recognizes that not all madness is created equal. At 244d, he argues that madness sent by a god is finer than human self-control. After a lengthy discussion of the nature of the soul and related topics, Socrates describes the kind of madness that characterizes the lover as “…that which someone shows when he sees the beauty we have down here and is reminded of true beauty; then he takes wing and flutters in his eagerness to rise up, but is unable to do so; and he gazes aloft, like a bird, paying no attention to what is down below—and that is what brings on him the charge that he has gone mad.” The passage quoted above that is read by Charles Laughton in Knight of Cups is actually cobbled together from passages that are separated in the text, including part of this one.[11] The recording elides Plato’s reference to madness, but there is a clear allusion to this notion in the same segment of the film (“The Moon”). Della, the woman that this segment focuses on, says, “You think I could make you crazy. Crack you out of your shell. Make you suffer.” Like Ben Affleck’s character in To the Wonder, Rick is presented as distant and withholding on account of his fear of transcending the safety of his illusory world and letting himself be carried away by erotic longing for something higher. She also says, “You don’t want love; you want a love experience.” Again, in Plato’s metaphysics there is a division between true reality and the illusory world of experience, and Della sees Rick as someone who is afraid of authentic love and is only open to a pale imitation of it.

Throughout the film, Malick repeatedly incorporates images of wings and of flight, particularly at moments when Rick and others can be understood as being “reminded of the beauty their souls once knew in heaven.” Once you’re looking for it, you’ll find that it’s everywhere. For instance, at the beginning of the second segment of Knight of Cups (“The Hanged Man”), Rick asks “how do I begin?” and we pan up to a flock of birds flying in a V-shape. In Chapter IV (“Judgment”) Rick and his ex-wife Nancy (Cate Blanchett) watch planes taking off and soaring over the desert. In Chapter VI (“The High Priestess”), Rick visits Las Vegas and is transfixed looking up at an aerial dancer. In Chapter VII (“Death”), featuring Natalie Portman as Elizabeth, we see the lovers holding out their arms on the beach in imitation of flight. This is far from an exhaustive list. As I will discuss in the second part of this paper, this motif carries over into Song to Song.[12]

The thought that all of these observations build towards, again, is that the many commentators who have thought that Knight of Cups is a movie about the way the people Rick meets in Hollywood drag him down and stunt his spiritual growth have it backwards. As Brian Dennehy (playing Rick’s father) narrates near the end of the film, “Find the light you knew in the east as a child. The moon, the stars, they serve you. They guide you on your way. The light in the eyes of others. The pearl.” This line—arguably the most important line in the film—ties together the Hymn of the Pearl, Pilgrim’s Progress, and the Phaedrus. Rick is a pilgrim stuck in the swamp. He’s a prince who’s forgotten his quest. The light in the eyes of others is here equated with the pearl that he must remember in order to awaken and resume his quest. In the final chapter of the film, titled “Freedom,” Rick becomes involved with the most positive figure in the film, Isabel. Interestingly, “Freedom” is the one chapter that is not named after a tarot card. I’m not sure what to make of this except that it was evidently important to Malick that the final chapter title convey the specific idea of freedom. This idea could have been signaled by several different tarot cards, but these cards might have resonances that he did not want to convey. The last line of Knight of Cups is a single word, spoken by Rick: “Begin.” He presumably means that he is finally prepared to begin the process of spiritual reawakening—the quest for the pearl that he has now remembered. He has gained the freedom to do this in part through the influence of his amorous adventures. Far from bogging him down, the beauty in the eyes of others is the beacon that has led him to begin his ascent.

***

The concept of freedom is at the center of Song to Song, and I think that we can make better sense of the importance of this concept in Knight of Cups by turning now to the later film. Like Knight of Cups, Song to Song is heavily referential. Whereas the two primary sources for the first film are Pilgrim’s Progress and the Hymn of the Pearl, the second film draws heavily on Milton’s Paradise Lost and Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Jonathan R. Olson, in his paper, “Milton’s Satan in Malick’s Song to Song,” has already done the work of reconstructing these references, and so my main focus here will be the relevance of Plato’s theory of love.[13]

The surface narrative of Song to Song is very simple. BV (Ryan Gosling) is a talented songwriter in Austin. Cook (Michael Fassbender) is a powerful music mogul who has his hands in everything. Faye (Rooney Mara) has worked for Cook as low-level staff since she was a teenager, and is now sleeping with him. In a Faustian bargain, Cook offers BV success, but under exploitive terms. BV and Faye meet at party at Cook’s house and start a relationship. She doesn’t tell BV that she has an ongoing sexual relationship with Cook. Cook meets a young waitress named Rhonda (Natalie Portman) and becomes smitten with her. He showers her with money and gifts and convinces her to marry him. Rhonda is religious, and feels deeply alienated by the world of sex and drugs that she now feels trapped in. She eventually commits suicide. Meanwhile, BV realizes that Cook was taking advantage of him, backs out of their arrangement, and finds out that he’s been sleeping with Faye all along. Faye and BV split up and have relationships with other people. Eventually, they reconcile and leave Austin and its music scene behind to live a simpler life out west, focusing on family and other responsibilities that they had previously sought to avoid.

There is decisive evidence that Cook, Michael Fassbender’s character in the film, is a Lucifer figure. Malick directly told Fassbender that his character is Satan from Paradise Lost.[14] The film is full of references to both Milton’s poem and Doctor Faustus. At one point, Faye as narrator refers to him as “Devil.” When he offers to help Rhonda and her family out of financial trouble and asks to marry her, we cut briefly to a shot of him holding a horned skull in front of his face. We see him making an effort to attend church with Rhonda (who is religious), but he is visibly uncomfortable and leaves her there alone. Soon after, he gives her hallucinogenic mushrooms dipped in honey, and the dissonant score and abrasive cinematography suggest that she has entered a worldly hell. During her trip, we see a tattoo that reads “Empty Promises,” and Cook narrates, “Open your eyes. You won’t die. Here I reign. King.” This is a clear reference to Satan’s third speech in Paradise Lost.[15] Shortly afterwards, Rhonda and Cook meet a man who has used various forms of body modification to make himself resemble a snake. There are also other narrative connections to Milton. For instance, the ending of the film, where Faye and BV forgive each other and recommence their relationship, mirrors the reconciliation of Adam and Eve.

Interpreting Song to Song holistically requires attending to the interplay between its layers of literary reference. My limited aim here is to elucidate the relevance of the Platonic theory of love. This is only one layer, but it is an important one, and its importance is less obvious here than it is in Knight of Cups. In particular, considering the relevance of the metaphysical dimension of Plato’s theory of love illuminates the significance of Malick’s depiction of Cook/Satan as a deceiver, and also the way in which Platonic love can remedy such deception.

Given that there are no explicit, direct references to Plato in Song to Song, this connection may seem far-fetched. If we take Knight of Cups and Song to Song together, however, the continuing relevance of Plato is obvious. The motif of wings and flight from Knight of Cups is continued very strongly in the subsequent film. At one point, Faye and BV take a trip to Mexico on Cook’s private jet. The two of them spend a half hour alone together at one point, and Faye thinks of this experience as the point where she fell in love with BV. As narrator, she tells us, “Everything came out of that half hour.” The lovers see a flock of birds during their whirling romantic stroll on the beach and meet a man who uses a bird to read their fortunes. Faye references this later in the film when the two of them are separated and she is longing for him, “I don’t like to see the birds in the sky because I miss you. Because you saw them with me.” With Knight of Cups as context, we should take this as an allusion to the notion from the Phaedrus that erotic love reminds us of the time when our soul had wings and restores in us the urge to fly up above the world of experience towards a higher reality. The birds are reminders to Faye of the glimpse of something higher that she experienced with BV before being dragged back down to Cook’s world.

BV and Fayre’s ethereal birdwatching experience in Mexico is contrasted with their flight home on Cook’s jet. The plane flies in a pattern to give the passengers the experience of weightlessness. They revel in it. This extravagantly expensive imitation of the experience of flight—which is itself an imitation of spiritual ascent—is a form of deception. What BV and Faye experience in their transcendent half hour is a glimmer of authentic spiritual elevation. They are reminded of when their souls had wings. Their ride on Cook’s plane substitutes an illusion for the thing itself. The motif comes up again when Faye finally admits to BV that she’s been sleeping with Cook all along. BV and Faye have sex on a table while a string of wooden birds (a mocking imitation of the birds they saw when they fell in love) hangs down above them. This encounter is less tender and more violent than their relationship has been up to this point. We cut briefly to BV in a field with a shotgun, bird hunting (!), before cutting back to him as he narrates that he became cold towards Faye and decided to leave her.

Song to Song develops a dichotomy between Cook’s world—the urban music scene—and the world of family and obligation. Faye and BV have both left their families behind to live in Austin. Faye feels ashamed that she hasn’t been as pious a daughter as her sisters, and BV has only recently escaped a chaotic home situation where he has been estranged from his father (who is insinuated to have been abusive or neglectful), his mother has been struggling with depression, and his brother has been acting out in troubling ways. The music scene is seen by Cook, BV, and Faye as a locus of freedom. BV mentions getting “free of this man,” in reference to his father. BV and Faye are described both by themselves and by Cook as desiring freedom. Cook offers BV, Rhonda, and Faye each a Faustian bargain in the film. For BV and Faye, it is a record contract and a pathway to making a living in the music industry. For Rhonda, it is financial support that will enable her to stop working low-paying jobs and fretting about how to take care of her mother. In all three cases, what Cook offers is explicitly related to the concept of freedom. This must be of course understood in reference to Paradise Lost, where Satan’s variety of freedom is contrasted with the authentic freedom of obedience to the divine will, but the Platonic context is also relevant. Cook’s freedom is merely an illusion of freedom—an image of the real thing. In the early stages of seducing Rhonda, he takes her for a drive in his Ferrari and asks her, “Do you like physical things?” The choice of words here is telling. Malick is drawing attention not simply to the emptiness of the satisfactions afforded by material luxury, but more deeply to the way that Cook’s illusory brand of freedom is tied to a focus on our embodied condition rather than our spiritual nature.

Faye elaborates what she understands freedom to be, “We thought we could just roll and tumble, live from song to song, kiss to kiss.” At another point, she says, “I wanted to escape every tie, every bond.” Cook’s freedom is a form of rootlessness, where one can leave behind obligations and responsibilities (financial, familial, and otherwise) and stay blissfully immersed in the moment. It is a “weightless” way of being. We see intoxicating images of music festivals where revelers are enthralled in a Bacchic frenzy. After taking a chainsaw to an amplifier on a festival stage, cutting his own hair off with a knife, and throwing fake uranium at the audience, Val Kilmer soliloquizes over the PA, “The music’s all about feeling free—so you don’t have to do nothing to be free!” This is as clear a statement as we could hope for of the Platonic significance of Malick’s dichotomy of freedom. It could even be taken in connection with the Platonic concern expressed in Republic X that poetry and other forms of mimetic art are dangerous in the way they can lead the soul to confuse an imitation for the real thing. Not long before Rhonda’s suicide, she has a conversation with a sex worker who Cook has hired to join them in bed. The sex worker explains, “I sell a fantasy, not my body. I sell an illusion.” Rhonda quietly asks as narrator, “is that me?” Cook’s world is nihilistic. When he appraises his estate, he admits, “This—none of this exists…. It’s all just free fall.” Cook’s freedom stands to true freedom as the experience of weightlessness in his luxury jet stands to authentic spiritual ascent.

Ultimately, BV and Faye will find true freedom not in Cook’s world, but in the practice of mercy and the embrace of spiritual love and the obligations and responsibilities that it grounds. BV has a much easier time leaving Cook behind than Faye does. From the start, he imagined himself writing songs based on his own painful experiences that would lift other people up and bring them joy. Once he sniffs out Cook’s exploitive intentions, he bails straightaway. Faye, on the other hand, is more ambivalent. She delivers the first line of the film as narrator, “I went through a period when sex had to be violent. I was looking for something real. Nothing felt real. Every kiss was half of what it should be.” We see Cook gripping her by the throat. She is not merely sleeping with Cook as a means to professional success; she is existentially adrift and searching for some form of authentic experience without being willing to accept the obligations and responsibilities that such experience would entail. Violent sex, in Faye’s self-understanding, substitutes intensity of experience for authenticity. It’s a form of self-deception not unlike the experiences that Plato labels as “false pleasures” at Philebus 45a-47d, because they create the illusion of being more pleasant than they actually are due to their admixture with pain.

Faye is more willing than BV is to knowingly immerse herself in illusion. “I wanted experience,” she narrates, “I told myself any experience is better than no experience.” Unlike BV, Faye explicitly thinks of herself as embracing something that is base—she is in this sense less deceived than he is. In one of her most striking lines, she admits, “I love the pain. It feels like life. Sometimes I admire what a hypocrite I am.” She recognizes and acknowledges her hesitancy to embrace the flickers of divinity she experiences with BV, but is not motivated straightaway to change. Plato explains in the Phaedrus what causes wings to fall away from the soul, “By their nature wings have the power to lift up heavy things and raise them aloft where the gods all dwell, and so, more than anything that pertains to the body, they are akin to the divine, which has beauty, wisdom, goodness, and everything of that sort. These nourish the soul’s wings, which grow best in their presence; but foulness and ugliness make the wings shrink and disappear” (246d-e). Using language that evokes this metaphor of flight from the Phaedrus in connection with the myth of Icarus, she says, “I pulled you down in the car. I didn’t believe enough in love. I was afraid it would burn me up.” She relates her hesitancy to embrace a more authentic form of experience with her attraction to the physical world, “I’m low. I like the mud. I don’t deserve you.” The world is a swamp that one must fly over (as Tonio put it in Knight of Cups), and Faye self-consciously embraces its foulness.

Faye’s condition is conveyed by an unidentified painting that we see briefly during Rhonda and Cook’s mushroom trip. The painting depicts a woman with wings and a mask, lying on her back as she looks into a small handheld mirror. Cook narrates, “The world wants to be deceived.” This painting could not have been more perfectly chosen. Human nature is made for something higher—our souls in their original state had wings—but, like the prisoners in Plato’s cave, we are too fixated on ephemeral reflections to look towards a higher reality. The figure in the painting ignores the vast sky above and neglects her ability to soar into the heavens. What she attends to instead is not even a reflection of her own face; it is an image of the false mask she shows to others. It’s a distorted reflection of a distorted imitation.

I take this contrast between BV and Faye to be central to what the film is about. It’s a love story between a Satan sympathizer and a spiritual seeker. She signals her allegiance when she narrates, “I revolted against goodness. Thought it had deceived me.” Much like Knight of Cups, Song to Song is about the way that erotic love can lift the spirt and reorient us towards something higher, but while Knight of Cups is about the onset of spiritual awakening, Song to Song is about what such an awakening looks like in action. The earlier film ends with the word “begin.” Song to Song shows us a beginning.

At the end of the film, Faye leaves Austin to start a life with BV, who abandons the music business to work in the oil fields and mend his family relationships. In a scene that I find so powerful I can barely stand to watch it, he visits his sick father, who he has previously said he wouldn’t forgive and who he no longer prays for. His father appears to have had a stroke, and BV breaks down and weeps as he wipes crumbs of food from his shirt. Living in Cook’s world entails choosing rootlessness over the responsibility that comes from genuine connection with others. BV’s choice to leave Cook’s world behind is also a choice to do the difficult work of being part of a family, and to follow the way of grace introduced in Tree of Life.

Wonderfully, the angel figure who nudges Faye back towards BV after their falling out is the great Patti Smith, playing herself. She tells Faye about her own great love affair, which ended many years earlier when her spouse passed away. She urges her to fight for the man she loves. In the film’s climactic moment, as Faye makes the decision to return to BV, we simultaneously hear Patti Smith singing and Faye reading William Blake’s “The Divine Image.” Smith’s performance, in contrast to the sort of performance Cook favors, is the type of music that BV wished to create: music that lifts the spirit. Blake’s poem includes these thematically crucial lines:

For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is God, our father dear,

And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is Man, his child and care.

For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.[16]

Human beings—for Blake, Plato, and Malick—are mortal in one way but divine in another. Blake’s poem highlights that human beings reflect the divine image, and that “Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love” are essential to the nature of divinity and to the expression of the divine aspect of human nature. As Elisa Zocchi explores in her paper, “Terrence Malick Beyond Nature and Grace: Song to Song and the Experience of Forgiveness,” this moment brings Malick’s cycle of films full circle, evoking Tree of Life and the way of grace.

As Faye works towards her decision to return to BV, she narrates, “I never knew I had a soul. The word embarrassed me. I’ve always been afraid of myself. I thought no one’s there.” Faye’s embrace of Cook’s world involved a denial of her nature as a being with a soul. When she goes on to say, “I forgot what I am” we see an image of BV holding a string of paper butterflies up while a young girl smiles in wonder. This image evokes once again the idea from the Phaedrus that love reminds us not just that we have a soul, but that our soul once had wings. We see another image of birds. Faye recognizes at last what the soul’s wings are for. She narrates, “There’s something else, something that wants us to find it.” We cut to figures ascending a spiral staircase. When she returns to BV, we see a winged statue and she narrates, “It was like a new paradise of forgiveness.” Faye’s return to BV is more than a decision to return to a romantic relationship; it’s also the beginning of her own spiritual seeking. She is at much the same place as Rick at the end of Knight of Cups. Early in the film she narrates, “I love your soul.” Once she comes around to embracing this love, she moves past the material stages of the Platonic ascent.

***

The theme of mercy and forgiveness is not as prominent in Knight of Cups as it is in Song to Song, but it is there. During the “Hanged Man” section of Knight of Cups, we learn that—like Malick himself and the character of Jack in Tree of Life—Rick has two brothers and one of them has tragically died. Wes Bentley plays Rick’s living brother, Barry. Barry is troubled, and like BV in Song to Song, Rick feels conflicted about leaving his brother behind.

We can infer that Rick’s path towards authentic freedom, like BV and Faye’s, is to follow the way of grace. How, though, can the way of grace be understood as freedom? This is a vastly complicated question that requires introducing a great deal of theoretical apparatus beyond Plato to properly address, but we can sketch the basic idea. Weightless drifting without a higher purpose (“living from song to song”) is the antithesis of genuine freedom. If one has no commitments, one has nothing to unify one’s self and so one’s actions are free only in the sense of being aimless and disconnected from a robust locus of agency. Obedience to the divine will is not passive; it is an active embrace of a system of value organized by a unified conception of the good. Weightless drifting as a way of avoiding obligation and responsibility is not freedom, but rather a dissolution of the self. As Rick’s father Joseph (Brian Dennehy) narrates in Knight of Cups, “I suppose that’s what damnation is. The pieces of your life never to come together, just splashed out there.” True freedom for Rick would first entail becoming a self, unified around a sense of purpose. Becoming one’s true self entails following the way of grace and emulating the divine image.

On my interpretation, these films are in part about the way that erotic love can prompt spiritual awakening. In Song to Song, we see such an awakening depicted in more practical terms. I take the key to understanding the relevance of the Platonic myths of Eros to the ending of Song to Song to be the dichotomy that Malick draws between Cook’s world and the world of family and obligation. Cook’s world embraces illusion. As Cook himself says, “None of this is real, it’s all just freefall.” Living in Cook’s world entails suppressing a fundamental aspect of our nature. We are not just worldly beings; we are also divine. The path to our higher nature is through mercy, love, and spiritual seeking, which express the manner in which humanity is an image of divinity. The way of life that BV and Faye set out upon at the end of the film shirks Cook’s world and embraces their real condition as beings with the capacity for grace, embedded in a network of human relationships that generate meaningful responsibilities and obligations that they willingly embrace. This is genuine freedom.

[1] E.g., https://reelentropy.com/2016/03/28/experimental-terrence-malick-trilogy-ends-with-a-bang/.

[2] https://www.bkmag.com/2017/03/17/song-to-song/. Sinnerbrink (2019).

[3] https://www.texasmonthly.com/arts-entertainment/the-not-so-secret-life-of-terrence-malick/

[4] Sinnerbrink, Robert. Terrence Malick: Filmmaker and Philosopher.

[5] ‘The Promise of Love Perfected: Eros and Kenosis in To the Wonder’ in Theology and the Films of Terrence Malick, edited by Barnett and Elliston, 235–6.

[6] I agree with Sinnerbrink that the Platonic theory of love is also in the background in To the Wonder, but my impression is that this film is more distinct from the other two than they are from each other.Aside from its obvious difference in setting (the latter two films both being set amidst the entertainment industry), To the Wonder is notably distinct in its emphasis on themes that are specific to Catholicism (e.g., the Church’s understanding of Marina and Neil’s relationship as adultery, which forces them to hold their marriage ceremonies first in civil court and then in a Protestant church, and the connection between spiritual love and openness to new life). Because of the complexities that these differences introduce, and because of limited space, I prefer to focus on Knight of Cups and Song to Song in this chapter and punt on the question of how To the Wonder fits into my analysis.

[7] https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/03/knight-of-cups-malick-review/472050/

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7ANslOvACE&ab_channel=CharlesLaughton-Topic

[9] Aside from the Phaedrus passage read by Laughton, which uses Christopher Isherwood’s translation, all quotations from Plato use The Complete Works of Plato, ed. John M. Coooper.

[10] Some commentators critique Knight of Cups on feminist grounds. See, for instance, David Ehrlich’s review: https://slate.com/culture/2016/03/terrence-malicks-knight-of-cups-starring-christian-bale-reviewed.html). A feminist critique may indeed be valid and important, but at least in this case it is premature. Before we can think about whether feminist consideration raise issues concerning Knight of Cups, we first need to understand what the film is about and how the relevant content functions. Ehrlich hasn’t even really attempted this. His critique begins from his initial impressions of the film’s surface content. I do not dismiss the importance of a potential feminist critique, but I set it aside in order to first try to understand what Malick is trying to do on its own terms.

[11] NB, The Laughton recording uses a translation by Christopher Isherwood, which is somewhat looser than the Nehamas and Woodruff translation that I quote here

[12] It is also present in To the Wonder, though my impression is that it is considerably less prominent in that film.

[13] Global Milton and Visual Art. https://books.google.com/books?id=rkMjEAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

[14] https://www.moviemaker.com/michael-fassbender-song-to-song-malick-lubezki/

[15] Here at least/We shall be free; the almighty hath not built/Here for his envy, will not drive us hence/Here we may reign secure, and in my choice/To reign is worth ambition though in hell/Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven.

[16] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43656/the-divine-image